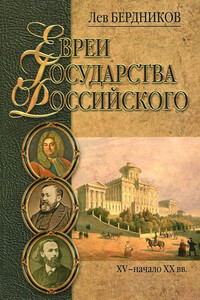

Евреи в царской России. Сыны или пасынки? | страница 6

Thus the Jewish doctor of Venice, Leon Mistro, was brought in to minister to Ivan Ill's ailing young son. Mistro treated the heir honestly and unselfishly, but the treatment was unsuccessful, and the unlucky healer was beheaded. He had been caught in the middle of a conspiracy: the heir had been poisoned and Leon tricked into trying to cure a non-existent disease. A similarly tragic fate befell another Jewish doctor – Stefan von Gaden, who was probably the best doctor at the tsar's court. He was accused of poisoning Tsar Fedor Alekseevich and killed after brutal torture.

Faithful sons thus shared the fate of hated stepchildren. But of course not all Jews experienced such unhappy endings. General Mikhail Grulev, for example, became one of Russia's most prominent military leaders and died peacefully at the age of 86. But he, as a Jew, had to endure a lot on the way to the heights of military glory. Equally difficult were the lives of the artist Moses Maimon, the writer Victor Nikitin, the folklorist Paul Shane, the famous photographer Konstantin Shapiro, all of which are described in this book.

To achieve success in any sphere of Russian life and prove that they could identify themselves as «true sons of Russia», Jews often had to make a very difficult step – to accept baptism. As the historian Simon Dubnov formulated this difficulty: «for Jews the only way to win the favor of the government was to bow before a Greek cross». Because of the laws limiting Jews to the Pale of Settlement and severe restrictions against living in large cities, getting a university education, taking part in professional activities, and so on, a baptismal certificate served as a ticket to the larger world and a better life.

Changing faith is always a very difficult and delicate process. It was especially difficult for Russian Jews because after conversion they almost invariably found themselves between a rock and a hard place. Their former coreligionists accused them of the greatest possible sin for a Jew, betraying their people; converts were considered dead and ritually mourned. Christians, on the other hand, looked on them with suspicion, considering their conversion fictitious and possibly even as a satanic way of destroying Eastern Orthodoxy from within. To prove their loyally baptized Jews sometimes endeavored to be «holier than the pope», trying to demonstrate their hatred for their former compatriots; such were branded with the contemptuous label «vykresty» (cf. «conversos» or «Marranos» in Spain). Some of these, like Johann Pfeferkorn and Jacob Brahman, and others who lived in different periods, played very sad role in Jewish life, e.g., slandering their fellow Jews and claiming the anti-Christian nature of the Talmud and other Jewish writings. And there were those like Paul Veinberg who mocked his fellow tribesmen in vicious caricatures, fueling Judeophobia in Russia.