Евреи в царской России. Сыны или пасынки? | страница 5

How to preserve one's Judaism and still remain a Jew and law-abiding citizen in one's country of residence? The Jews had to deal with this question for centuries, to develop a special way of dealing with the powers that be and with the predominantly hostile population. Very early, even in the Talmud, the principle for life in the Diaspora was «dina de Malchut – Din» or following the law («the law of state is the law», Nedarim 28a Gittin 10b). Jews consistently obeyed this obligation and served their new homelands conscientiously, if often without reciprocity.

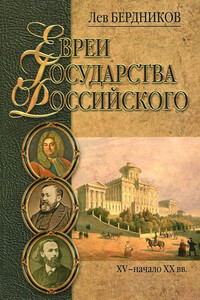

All of this fully applies to the life of Jews in Russia. They lived in Slavic lands from ancient times – from the era of Kievan Rus. We know the names of many Jews who were in one way or another connected with Muscovite Rus' and then with the Russian state during the fifteenth through seventeenth century. But the central act in the historical drama of the Jews in Russia starts with the glorious times of Peter the Great and especially Catherine II. After Russia's partitions of Poland, these lands, together with the former territories of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, combined to create in the Russian Empire the largest Jewish community in the world. Since that time, the fate of the Jews and Russians on Russian territory became inseparable, interwoven in most intimate ways.

Jews in Russia had much to endure – including hard life in the ghetto, humiliation and persecution, and at times blood libels and horrifying pogroms. But at the same time the Jews provided Russia with many outstanding citizens and true sons of the fatherland – generals, poets, scientists and businessmen. Over the centuries a special Jewish-Russian intelligentsia culture was born, with its own unique «Jewish-Russian» cultural atmosphere. But the prominent role of many Jews in Russia did not prevent them from often being treated as second-class citizens, always at risk of being humiliated.

These are the issues Lev Berdnikov describes in his new book, trying to solve the eternal question: have Jews in Russia been its children or its stepchildren? The tragic dualism of Russian Jewry is suggested by the book's two epigraphs, by Saul Gruzenberg and Alexander Gorodnitskii, each of whom sees the fate of the Jews from his own point of view. Starting with the Jews of Muscovy, the author leads us down Russia's historical path, along which Jews left many significant marks but invariably found themselves in a kind of limbo, suspended between the roles of children and stepchildren.