Евреи в царской России. Сыны или пасынки? | страница 7

But even if Jews sincerely wished to join the new community, they were often mistrusted. The historian of Spanish Jewry Benzion Netanyahu has claimed that the Spanish Jews were not baptized under compulsion, but willingly and consciously, wanting to assimilate into Spanish Christian culture. Nevertheless, Christians still hated the «Marranos» and suspected them of a variety of sins.

And baptism did not save them from the hatred of anti-Semites, or sometimes even from death. This applies to some of the Jews described in this book as well as to many others. Since their school years the prominent economist Mikhail Gertsenshtein and the journalist Grigory Yollos had been friends. The former was baptized while the latter preserved his Jewish faith. Both were Russian patriots, its true sons, and both became members of the first state Duma in 1906; in questionnaires they described themselves, respectively, as «Jew of the Orthodox Confession» and of the «Russian Jewish faith», And both were murdered by killed by the Black Hundreds as Russia's despised stepchildren.

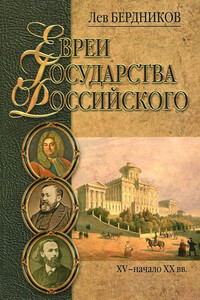

Lev Berdnikov carefully analyzes the biographies of Russian Jews who became famous and made significant contributions to the life of prerevolutionary Russia. Naturally, many of them adopted Christianity. But there is a common myth, particularly characteristic of the Orthodox Jewish community, that Russian Jews' change of faith was always a cynical move in order to improve their siuation, as echoed in the statement attributed to the outstanding Orientalist Daniel Khvol'son: «Better to be a professor in St. Petersburg than a melamed in Eyshishke». To the contrary, many Jews consciously accepted Eastern Orthodoxy, identifying it with Russian culture, and there were those who genuinely converted to Christianity without harboring any bad feelings toward their people.

The author explores the internal struggles, painful reflections, and complex life paths of Jews who converted to Orthodoxy but did not forget about their Jewishness. And he has created a truly unique work. There are scholars of Russian history who pay special attention to Orthodox-Jewish relations, but usually they are focused on very specific, narrowly scholarly issues. These studies are important, but only Lev Berdnikov raises broader questions of the nature of those relations, based on the lives of those who experienced them, and, furthermore, he presents his arguments for the consideration of a broad, socially-conscious public. To do this he aims to combine, as far as possible, the thoroughness of biographical research with a popular and entertaining style – something in which he certainly succeeds.