Best Short Stories | страница 71

His mother noticed how overwrought he was.

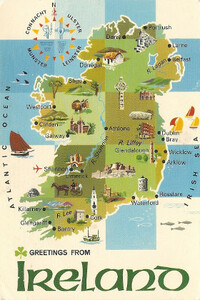

‘You’d better go to the seaside. Wouldn’t you like to go now to the seaside, instead of waiting? I think you’d better,’ she said, looking down at him anxiously, her heart curiously heavy because of him.

But the child lifted his uncanny blue eyes.

‘I couldn’t possibly go before the Derby, mother!’ he said. ‘I couldn’t possibly!’

‘Why not?’ she said, her voice becoming heavy when she was opposed. ‘Why not? You can still go from the seaside to see the Derby with your Uncle Oscar, if that’s what you wish. No need for you to wait here. Besides, I think you care too much about these races. It’s a bad sign. My family has been a gambling family, and you won’t know till you grow up how much damage it has done. But it has done damage. I shall have to send Bassett away, and ask Uncle Oscar not to talk racing to you, unless you promise to be reasonable about it: go away to the seaside and forget it. You’re all nerves!’

‘I’ll do what you like, mother, so long as you don’t send me away till after the Derby,’ the boy said.

‘Send you away from where? Just from this house?’

‘Yes,’ he said, gazing at her.

‘Why, you curious child, what makes you care about this house so much, suddenly? I never knew you loved it!’

He gazed at her without speaking. He had a secret within a secret, something he had not divulged, even to Bassett or to his Uncle Oscar.

But his mother, after standing undecided and a little bit sullen for some moments, said:

‘Very well, then! Don’t go to the seaside till after the Derby, if you don’t wish it. But promise me you won’t let your nerves go to pieces! Promise you won’t think so much about horse-racing and events, as you call them!’

‘Oh no!’ said the boy, casually. ‘I won’t think much about them, mother. You needn’t worry. I wouldn’t worry, mother, if I were you.’

‘If you were me and I were you,’ said his mother, ‘I wonder what we should do!’

‘But you know you needn’t worry, mother, don’t you?’ the boy repeated.

‘I should be awfully glad to know it,’ she said wearily.

‘Oh, well, you can, you know. I mean you ought to know you needn’t worry!’ he insisted.

‘Ought I? Then I’ll see about it,’ she said.

Paul’s secret of secrets was his wooden horse, that which had no name. Since he was emancipated from a nurse and a nursery governess, he had had his rocking-horse removed to his own bedroom at the top of the house.